Simone Biles of Team United States celebrating on the podium during the medal ceremony for the Artistic Gymnastics Women’s Vault Final is projected as part of Parisienne Projections on August 03, 2024 in Paris, France. Photo by Carmen Mandato/Getty Images

What a year in sport was 2024. In addition to the major sporting events we’re glued to every year like The Super Bowl, March Madness, Wimbledon, The Masters, The World Series, The Stanley Cup, and more… this was a summer Olympic Year. The 45 sports of Paris 2024 were like a year’s worth of competition crammed into 16 days. You also had the UEFA European Football Championship that for soccer fans is as big as the World Cup.

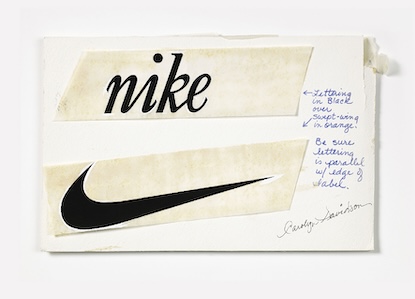

Getty Images and their seasoned roster of sport photographers were there to capture it all – every second of every sporting event, all year long. We spoke with Michael Heiman, VP of Global Sport who shared picture by picture what it takes to document all these unforgettable moments – not just the action, but the emotions too – and get them out into the world seconds after they happen. Every picture tells a story. Read More